Abstract

This paper summarizes the results of efforts to bring attention to the importance of understanding and improving groundwater governance and management. Discussion of survey work in the United States and global case studies highlights the importance of focusing attention on this invisible water resource before pollution or depletion of it causes severe economic, environmental, and social dislocations. Better governance and management of groundwater are required to move toward sustainable groundwater use.

Introduction

The growing population’s increasing demand for water for food, energy, and other human uses and changing climate’s impacts to both water supplies and demands are resulting in increasing reliance on groundwater. In many places groundwater is being depleted faster than nature replenishes it, and its quality is being compromised. Groundwater “mining” can have negative implications for meeting long-term water needs of people and natural systems. At the same time that groundwater from deeper and saltier aquifers is eyed for meeting future drinking water needs, aquifers are being identified as repositories for waste streams from desalination and energy processes as well as carbon sequestration sites. As dependence on groundwater increases, water managers and policy makers must pay careful attention to both groundwater quality and quantity. This paper focuses on efforts to bring attention to the importance of understanding and improving the governance and management of this invisible and increasingly relied-upon resource. It is essential that water users focus attention on this invisible water resource before pollution or depletion of it causes severe economic, environmental, and social dislocations. Better governance and management of groundwater are required to move toward sustainable groundwater use.

Multi-disciplinary and collaborative efforts to bring attention groundwater management and governance

In 2011, global leaders in groundwater monitoring and management embarked on an effort to highlight best practices in groundwater governance. Completed in 2016, the Groundwater Governance Project “aimed to influence political decisions thanks to better awareness of the paramount importance of groundwater resources and their sustainable management in averting the impending water crisis”.1 The three final project documents and extensive background documents2 provide a rich overview of the issues associated with managing groundwater at different geographic scales. The stated need for this project on groundwater governance was predicated on the rapid increase in groundwater extraction and its invisibility. Unlike surface water, which can be seen and touched separately from its consumption, water consumers generally have little understanding of groundwater quantity and quality.

I will note here that there are about as many definitions of (ground)water governance as there are papers or books written on it. I like to use the following single-sentence definition, which I developed with coauthors: Groundwater governance is the overarching framework of groundwater use laws, regulations, and customs, as well as the processes of engaging the public sector, the private sector, and civil society.3 This framework shapes “what” is done, that is, how groundwater resources are managed and how aquifers are used.

I had the good fortune of being invited to participate in the regional consultation portion of the project, where water management professionals from around the world were invited to participate in one of five regional consultations. The consultations were held in Uruguay, Kenya, Jordan, China, and the Netherlands. It was for the final regional consultation held at The Hague in March 2013, where United States (US) practices would be shared, that I was motivated to characterize the US’ decentralized approach to groundwater governance. I will report more on the efforts to describe US groundwater governance and management in the next section.

In 2016, two independent efforts, one in the United States and the other more globally based, attempted to bring greater attention to the importance of wise governance and management of this invisible resource through dialogues from which principles or directives emerged. The American Water Resources Association (AWRA) and the National Groundwater Association, two US-based national organizations dedicated to knowledge sharing, education, and good water stewardship, joined forces and convened the April 2016 Groundwater Visibility Initiative workshop. I was on the workshop organizing committee and contributed to the efforts to disseminate workshop findings. The six summary principles are as follows:4,5 (1) Governing and managing groundwater require working with people; (2) Data and information are key; (3) Some “secrets” remain; (4) We need to take care of what we have; (5) Effective groundwater management is critical to an integrated water management portfolio that is adaptive and resilient to drought and climate change; and (6) To be robust, policies of the agriculture, energy, environment, land-use planning, and urban development sectors must incorporate groundwater considerations. Perhaps most wide-ranging of the findings-conclusions is the recognition that effective groundwater management is critical to an integrated water management portfolio that is adaptive and resilient to drought and climate change. In addition, the importance of groundwater considerations to policies related to agriculture, energy, environment, land-use planning, and urban development was underscored. Fundamentally, the workshop concluded that it comes down to the relationship of the water consumers to the resource. Are they organized to manage the resource and, if so, on the basis of what information? A major thrust of this effort, like the global Groundwater Governance Project, was to bring attention to the important, growing, and often misunderstood status of groundwater in meeting human and environmental water needs.

The second effort emerged from the Ninth International Symposium on Managed Aquifer Recharge (ISMAR9), which was held in Mexico City in June 2016. A subset of groundwater experts from across the globe convened to draft a set of principles for sustainable groundwater management.6 The six principles or directives from this effort include stopping depletion of aquifers, acquiring and sharing information on aquifer systems, and managing groundwater within an integrated water resource framework. Specifically, the directives are (1) Recognize aquifers and groundwater as critically important, finite, valuable, and vulnerable resources; (2) Halt the chronic depletion of groundwater in aquifers on a global basis; (3) Aquifer systems are unique and need to be well understood, and groundwater should be invisible no more; (4) Groundwater must be sustainably managed and protected within an integrated water resource framework; (5) Managed Aquifer Recharge should be greatly increased globally; and (6) Effective groundwater management requires collaboration, robust stakeholder participation, and community engagement. It is not surprising that a group convened to explore managed aquifer recharge urged increased implementation of MAR efforts. Again, the importance of stakeholders was noted: Effective groundwater management requires collaboration, robust stakeholder participation, and community engagement.

While the Water Governance Initiative led by Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is not exclusively focused on groundwater, this initiative has also emphasized the role of stakeholder engagement.7,8 However, what is less recognized is that sustaining meaningful stakeholder participation is resource intensive. I still see very limited resources going into stakeholder engagement efforts.9 This is true at a time when professionals from multiple backgrounds are concluding that the barriers to agreeing upon a strategy to address many of the world’s thorniest water challenges are those related to the human dimensions of water sector decision-making rather than engineering or even financial constraints.

Most recently, in early 2018, the AWRA adopted its “Policy Statement on Fresh Groundwater”.10 The AWRA recommends that groundwater be managed according to the tenets of Integrated Water Resources Management and that attention focus on the following ten action items so as to advance sustainable groundwater management, presented here in abbreviated form: (1) Assessing the resource; (2) Building partnerships; (3) Aligning the legal framework; (4) Including groundwater considerations; (5) Maintaining sustainability; (6) Respecting ecosystems; (7) Engaging stakeholders; (8); Committing to understand; (9) Protecting the asset; and (10) Utilizing interdisciplinary approaches.

I am therefore encouraged that hydrologists, engineers, and other physical scientists are increasingly acknowledging the importance of collaboration across disciplines and the need for robust stakeholder participation.

Efforts to characterize and share US groundwater governance practices

What do we know about actual governance practices that lead to good groundwater stewardship? The Groundwater Governance Project had sharing governance practices at its foundation. It convened water managers and decision-makers from jurisdictions large and small, ranging from island states to large countries. This was necessary because groundwater is primarily a local resource. Approaches to its governance and management will reflect relevant laws and regulations, along with local physical and economic conditions. No cookbook approach to groundwater governance has emerged. What has turned out to be illuminating and helpful is the comparing of experiences so that decision-makers, water professionals and other can learn from each other’s successes as well as challenges.

As I participated in the more global dialogues, I observed something that bothered me. Often, conditions for the US were shown on a map in a single color, meaning that conditions were uniform across the US. Nothing can be further from the truth in a country as large as the US. While some may inherently acknowledge this, my guess was that few engaged in global discussions on groundwater governance and management recognized just how decentralized groundwater authorities and agencies are across the US. Despite the US being a nation of states, aside from national regulations addressing the quality of drinking water and discharges of water into navigable waters, there is little other federal guidance on groundwater quantity or quality. To help document the diversity of governance and management approaches across the US, a small team at the University of Arizona undertook an effort to characterize elements of this diversity. Armed with a survey of the literature that revealed no recent survey of state practices, we undertook an initial and survey of the states to demonstrate that one cannot paint the US groundwater governance and management picture with a single brushstroke.11 This survey targeted experts from state agencies responsible for water quantity regulations. One of the survey results was that most states had different government agencies managing water quantity and water quality.

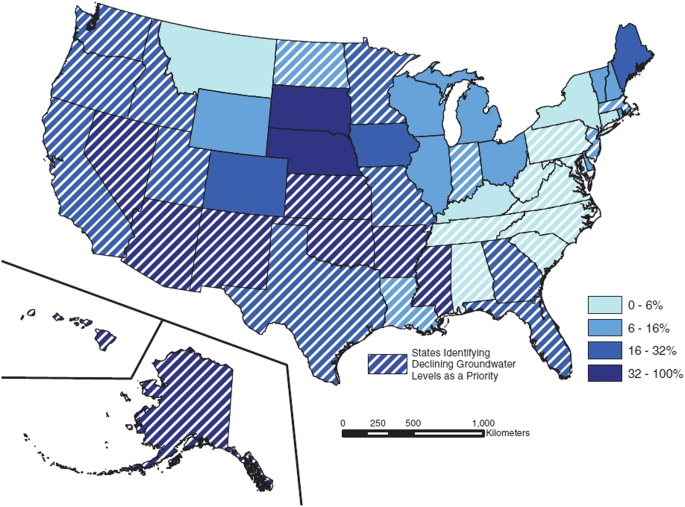

Figure 1 shows quite a bit of variation in reliance on groundwater across the US states. Indeed, within states there will be additional variation. Super-imposed on the coloring showing the level of extent of reliance on groundwater are hatch marks showing states that reported a focus on declining groundwater levels. Several states with limited reliance on groundwater for overall state water demands indicated concern with declining groundwater levels.

States’ reliance (as a %) on groundwater for total water withdrawals and states concerned with declining groundwater levels. (reproduced with permission from ref. 3, Copyright National Ground Water Association 2015)

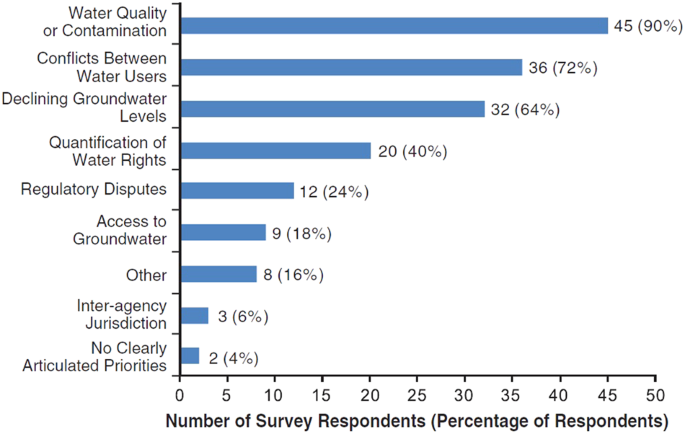

As Fig. 2 shows, water quality or contamination was the most frequently cited priority—even by personnel from state-level water quantity agencies. Because water quality determines the cost of using groundwater for different purposes, water quality and quantity are intrinsically connected.

Groundwater governance priorities. (reproduced with permission from ref. 3, Copyright National Ground Water Association 2015). The items listed, in order of frequency, were selected by respondents as their state groundwater governance priorities

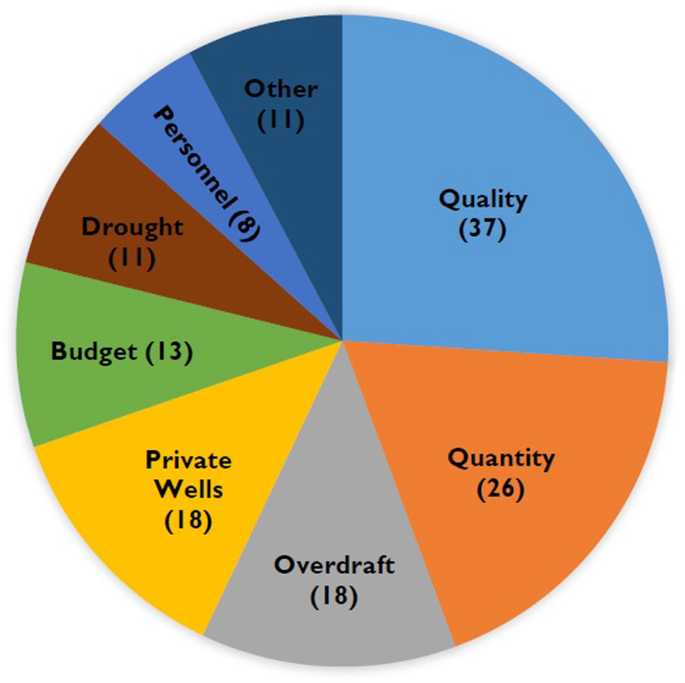

This finding was validated by a more recent national survey that focused on groundwater quality.12 For our “State-level Groundwater Governance and Management in the U.S.—Summary of Survey Results of Groundwater Quality Strategies and Practice”, we surveyed state water professionals primarily from water quality agencies. As summarized in Fig. 3, respondents identified several groundwater concerns, including impairment of water quality and quantity, staffing and budget issues, health/vulnerability of private well users, and aquifer overdraft, with water quality being the most frequently cited. Contamination of groundwater, especially in agricultural sites but also due to naturally occurring contaminants, was a key concern. Additionally, underground storage tanks, Superfund/CERCLA sites, industrial sites, and septic tanks were noted by many survey respondents. Nitrate and chlorinated solvents were the two most cited contaminants.

Frequency of groundwater concerns listed in the top three by states (Number responding = 48) (based on data from ref. 12)

Most respondents pointed to the existence of groundwater quality management goals and noted that significant changes to groundwater quality policy occurred in the past decade. Extensive information sharing of groundwater quality data was reported, with most states having groundwater quality standards and a groundwater classification system. States reported multiple sources of funding for water quality programs, with 85% depending at least in part on federal funding. However, states reported challenges associated with decreasing groundwater quality program budgets. Looking to the future, water quality/water level monitoring and increased groundwater pumping were identified as requiring additional attention.

Because both surveys targeted only one respondent per state, should resources be available, additional inquiry and analysis would help validate the results. Nevertheless, the results can indeed be used to portray the richness and diversity of groundwater governance and management issues faced across the US and aid those interested in understanding how experiences elsewhere relate to their own priorities, challenges, and policies.

Considerations of transboundary aquifers and groundwater governance case studies

Groundwater governance and management practices will reflect the geographic reach of aquifers, jurisdictional boundaries, and the rules and regulations set forth by the relevant nation, state, or locality. Special attention must be given to aquifers that cross boundaries (see ref. 13 for a summary of interesting cases and the myriad issues that arise). The almost 600 known transboundary aquifers are mapped by the International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre.14 The governance of transboundary aquifers must respect the sovereignty of nations, including tribal nations, and their different regulatory frameworks, cultures, and often languages. For over a decade, I have been involved in assessment of aquifers along the US-Mexico border. Collaborative assessment of transboundary aquifers is likely the precursor to transboundary governance and management because it is difficult to manage aquifers that have not been characterized through an agreed-upon methodology. The experiences of the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program (TAAP) along the US-Mexico border demonstrate the importance of establishing the rules of engagement for binational investigations. The cooperative framework developed for it can serve as a model for others undertaking similar efforts, whether across or within nations.15

Case study analysis is useful to identifying good practices and determining trends.16,17 While a survey or review of groundwater governance case studies is beyond the scope of this perspective article, a look at the case study section of the released volume, Advances in Groundwater Governance,18 is instructive. In addition to a chapter by this author and others focusing on the US,19 the section includes seven case studies from across the globe.

Habermehl explains how national legislation in Australia, the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act of 1999, which explicitly requires protection of groundwater-dependent ecosystems, applies to the Great Artesian Basin.20 Dinesh Kumar addresses how the sub-regions of the Indo-Gangetic Plains of India21, the “cereal bowl” of India, face distinct groundwater problems and management challenges due to their different physical, economic, and social characteristics. Two recommendations offered to help the sub-regions move to groundwater sustainability are pro rata pricing of electricity and a water rights system, both in conjunction with each other. Fried et al.22 consider the evolution of groundwater governance in the European Union and explain how science-policy dialogue over time has extended groundwater governance concerns to include environmental considerations and incorporate the connection between groundwater and surface water. The move from private ownership to public ownership of groundwater was a significant feature of the 1998 South African National Water Act.23

The chapter on the Middle East-North Africa region expresses pessimism regarding moving to sustainable groundwater governance and management due to ineffective state-level governance and limited participation of water users in improving the frameworks.24 The authors see continued depletion of groundwater systems, with the concomitant implications for water quality and cost of extraction. Amore25 emphasizes the multiple levels of actors in his discussion of the transboundary Guarani aquifer, which is shared by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. On the first page of his chapter, Amore emphasizes the complex inter-jurisdictional relationships when he writes about the Guarani Aquifer Project: “…the weakest and most crucial level to foster groundwater governance is the local or municipal level, because it is at this level that all contamination and overexploitation problems of the aquifer really occur. Many expectations are supposed to be resolved after the Guarani Aquifer Agreement’s enforcement; one of them is how regional and national level can effectively support the local level, a critical dimension to mitigate impacts and develop protection strategies to the Guarani Aquifer.” Finally, the chapter by Hirata and Escolero compares and contrasts the groundwater situation for the two largest metropolitan areas in Latin America – São Paulo, Brazil and Mexico City, Mexico.26 Mexico’s water supply is owned by the federal government, which has a water rights and permitting system and which allows for marketing of water rights. However, there, as in São Paolo, the governance framework is complex and fragmented, with the authors pointing to lack of enforcement capacity and ineffectiveness.

Returning to the US, although US groundwater regulation is determined by the states, some states further delegate authorities or responsibilities to regional districts or other sub-state jurisdictions, the Megdal et al. chapter in the Villholth volume highlights the experiences of two states—an early adopter and a late adopter of state-level groundwater governance frameworks. In 1980, Arizona, my home state, led the way in adopting comprehensive groundwater regulations for areas called Active Management Areas. California, with 38 million people, did not enact a statewide framework for groundwater regulation until 2014. With California being home to one of the largest economies in the world, attention is focused on the implementation of California’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.27,28 However, it is too early to report on the effectiveness of this recent legislation.

Neither Villholth et al. nor I can offer a recipe for those striving to achieve sustainable groundwater management. Returning to its local nature, strategies will depend on the local situation, including those related to community norms and values. Villholth et al. provide early acknowledgement of this when, in their Preface to ref. 18, they state: “The book does not present final conclusions or recommendations as no silver bullets exist for groundwater governance.”

Concluding remarks

Groundwater, the invisible water supply, is becoming more visible in dialogues on the challenges of meeting the world’s food, energy and water needs. The governance and management of this resource will often be at the scale of the source aquifers. Many across the globe are working hard to bring greater attention to the importance of good governance and management of this oftentimes non-renewable resource. As the state-level survey work demonstrates, quality considerations are paramount to those responsible for regulating groundwater. Along with other factors, quality considerations will determine groundwater’s usability. The case studies discussed underscore that groundwater is largely a local resource, with its governance and management vital to the livability and productivity of regions around the globe. Water policymakers, users, researchers, and citizens must focus attention on this invisible water resource before pollution or depletion of it results in severe economic, environmental, and social dislocations.

Contact us for more information.